Photo: Laura Hughes

The more that I study Nature, the more that I am convinced that one must really look hard at the LITTLE things. At least if one wishes to really develop a deep understanding of ecology, and how organisms are linked together. I am fortunate indeed that I have many friends who feel the same, and will give a caterpillar about the same attention that they would a goshawk.

In this photo, taken on a recent foray, David Hughes (front), John Howard (middle), and your narrator spend some time on the ground - not a rare occurrence for any of us. We were watching the bed of Partridge-pea, Chamaecrista fasciculata, plants that cover the bank in front of us. Numerous ants were visiting the extrafloral nectaries on the plants' leaf petioles, and we were watching them and attempting to obtain images. I wrote about ants and nectaries HERE, should you be interested.

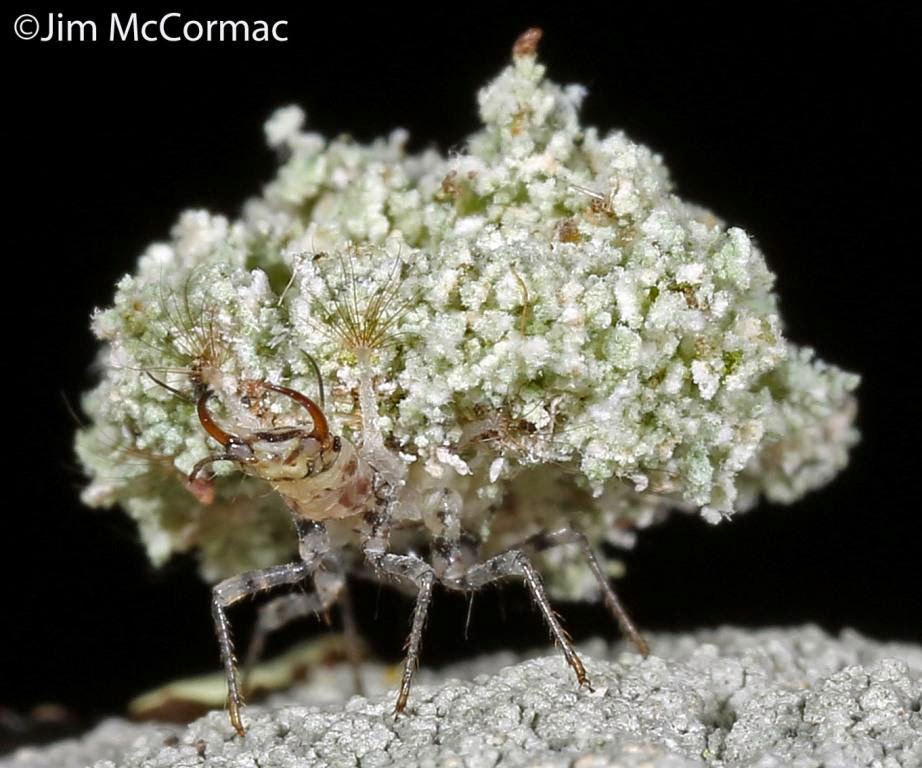

Well, this animal is also attracted to plants, and it is really tiny. It is a member of the Braconid wasp family, and is in the genus Lytopylus. I did not know such wasps existed until yesterday, when Cheryl Vargas spotted this animal on a trip to a west-central Ohio fen, and tipped me to it. The wasp looks big in this photo, but it wasn't much more than the size of a large mosquito. It is standing atop the still emerging disk flowers of an Orange Coneflower, Rudbeckia fulgida, and when I beamed in on it through the macro lens, I could see it was engaging in very interesting behavior.

If you look at the rear of the wasp, you'll see she's sticking her very long ovipositor into the flower cluster. I had not seen anything like this before, and could only speculate that she was going after tiny flower thrips, or perhaps some other concealed organisms. As an aside, I would say that Lytopylus wasps must also serve some function as pollinators, judging by all of the pollen stuck to her.

Once I returned home, a bit of research led me to her identity, at least to genus (as always, please feel free to correct me on identifications). There are a number of species in the genus Lytopylus, and identifying them to species is beyond me.

In this photo, we can see her ovipositor quite well. It juts from the rear of the abdomen, makes a few kinks, and then augers down deep into the clump of disk flowers. Female wasps (and bees) are equipped with "stingers", which come in lots of variations. Some can use them to sting, but the primary function is to lay eggs. The Lytopylus wasps are parasitoids - they lay their eggs on an animal host, and the wasp grub consumes the victim.

Apparently Lytopylus wasps are adept at ferreting out the locations of tiny moth caterpillars concealed within the disk flowers of Rudbeckias and similar species in the sunflower family (Asteraceae). The wasp bores down to them with her long wiry ovipositor, and deposits eggs. The caterpillar will fuel the wasp larva's growth, dying in the process. I suspect that these tiny wasps play a vital role in reducing flower predators. In the relatively short time that we watched her, she visited many coneflower blooms, presumably nailing caterpillars in all of them.

Amazing. At least to me.

The life and death drama that constantly plays out on flowers would be the stuff of science fiction, were it not true.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)